In Conversation with … Diana Jefferies PhD

Lecturer in the School of Nursing and Midwifery at the University of Western Sydney

By Alison Houston

Dr Diana Jefferies still finds it surreal that what she admits could once have been a dry academic research paper has taken on a life and personality of its own.

It was a meeting at last year’s Annual Arts and Health Conference with Taimi Allan, the CEO of mental health charity Changing Minds, involved in arts-based health promotion projects, that married Diana’s research into perinatal psychosis to the arts, resulting in the one-woman play Mockingbird.

Diana, a lecturer in the School of Nursing and Midwifery at the University of Western Sydney and a registered nurse with 25 years clinical experience, also has a PhD in English literature, but said she could never have foreseen the path her research would take.

“I still can’t believe it’s actually happening,” Diana said.

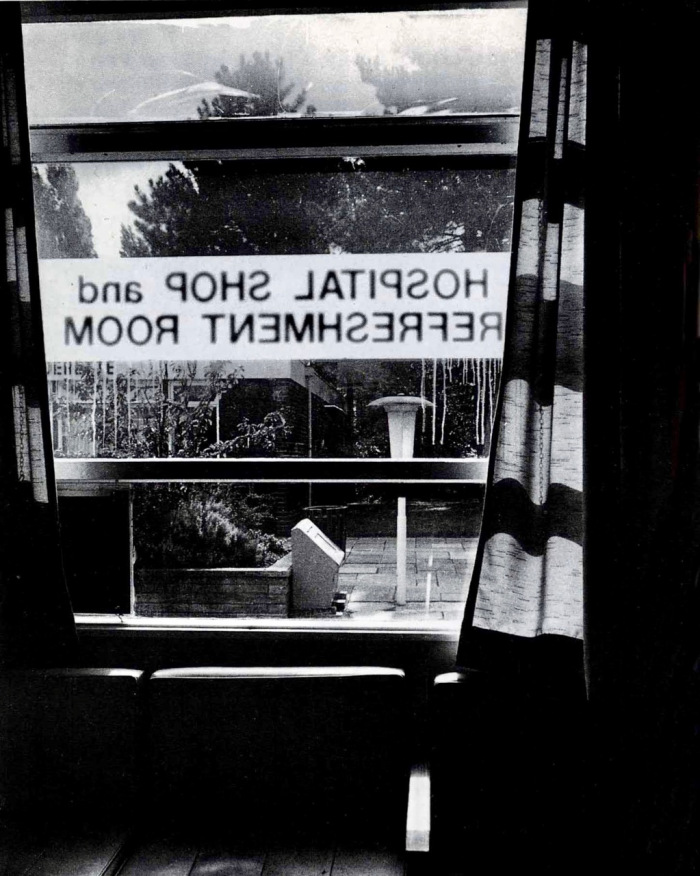

Mockingbird is a black musical comedy aimed at building awareness of perinatal psychosis and mania today by portraying what it was like for women admitted to mental health facilities with this diagnosis over the past 100 years.

“The conference really opened up a lot of new avenues and has been very important in showing how arts-based therapies can make a difference to people,” Diana said.

“The stories of the women I had researched were very academically written on the page, and would go to a very limited audience.

“Putting those stories into a play, those women come off the page and are given a body and voice, which is a far greater emotional experience.

“It shows how this sort of research can make a real impact on the world.”

With the help of writer and actress Lisa Brickell, Mockingbird was created as a series of 4-5 vignettes – an amalgam of 10-12 of the women’s experiences which Diana had researched.

Diana had examined the historical healthcare records of these women, highlighting the similarities and improvements in pre, post and peri-natal mental healthcare from 1885-2001.

She explained that although not publicly discussed, and often unrecognised even among the medical fraternity, 1-2 women in every 1000 will experience perinatal psychosis. That’s 600 women every year in Australia.

“I’m currently speaking to women who have had this experience in the past 10 years, and part of the problem today remains the lack of awareness regarding this condition,” Diana said.

“The mothers know something is wrong – psychosis involves sudden mood swings, hallucinations, confused thinking – but because people don’t realise when it is occurring, or are not correctly diagnosed until it is very severe, the woman often has to be admitted to a psychiatric hospital, where she is separated from her baby.

“Those mums want to be heard. They want the condition to be recognised, and they don’t want to be admitted to a psychiatric ward.

Diana said because so little was known about the condition, even maternity staff often didn’t recognise it, or really understand the woman’s needs.

“There is still a stigma that people don’t want to mention the word ‘psychosis’ in case it upsets someone,” she said.

While these women’s suffering is nothing to laugh about, Diana said by approaching their stories through black comedy it was easier for audiences to identify with them rather than being overwhelmed and unable to relate.

“It is better to make people laugh as well as cry for them to become really involved in a subject,” she said.

“This is all about getting the message out there into the world and to create change.

“I can get my papers published in as many nursing journals as I like, but it won’t have the same effect as bringing those stories to life for an audience.”

She hopes Mockingbird will bring about a new understanding between maternity and psychiatric divisions so that mothers can be given appropriate and timely treatment.

“This is a real illness that people need to recognise and start thinking about the best way to look after these women,” Diana said.

It’s hoped that when the play is performed in February, research surveys on the audience will quantify exactly what the play’s impact is.

- Diana is taking part in an oral presentation as well as a workshop and performance of Mockingbird: Understanding Postnatal Distress by using performance to engage audiences with real women’s stories over four generations with co-presenters Taimi Allan and Lisa Brickell at the 9th Annual International Arts and Health Conference – The Art of Good Health and Wellbeing – from October 30 to November 1 at the Art Gallery of NSW.